Why do so many cultures tell the same stories—floods, sky-fathers, underworld journeys—even when they’re oceans apart? Are myths just outdated religion, or is religion evolved mythology? In this post, we’ll explore how mythology and religion intertwine, diverge, and reappear across time. From Greek heroes to Abrahamic prophets, many figures wear the same symbolic robes—but for different reasons.

What’s the Difference Between Mythology and Religion?

Let’s start with definitions.

- Mythology refers to the body of traditional stories a culture tells to explain its world—its creation, moral order, and metaphysical forces.

- Religion, meanwhile, includes mythology but adds ritual, doctrine, and organized practice. It’s not just about stories, but how people live and relate to the divine.

In practice, mythology often becomes the “ancestor” of religion—or religion mythologizes itself over time. The same narrative may exist in both domains, interpreted differently depending on context and belief.

Shared Building Blocks: Common Motifs in Myths and Religions

![]() Across civilizations, we find recurring themes that bridge ancient myth and modern religion:

Across civilizations, we find recurring themes that bridge ancient myth and modern religion:

1. Creation from Chaos

- In Greek myth, Gaia and Uranus emerge from Chaos.

- In Mesopotamia, Marduk slays Tiamat to create the world.

- In Genesis, God brings order to a formless void (tohu wa-bohu).

▶ Common idea: The world arises from disorder, often through divine violence or speech.

2. Sky Father and Earth Mother

- Zeus and Gaia, Odin and Jörð, Uranus and Gaia, Anu and Ki.

- Even in Abrahamic religions, the masculine singular God is associated with the sky/heaven, while the earth is maternal in poetic metaphors.

▶ Pattern: Duality of order and fertility; masculine authority meets generative ground.

3. Flood Myths

- Gilgamesh, Deucalion and Pyrrha, and Noah all survive divine floods meant to reset humanity.

- Floods symbolize both punishment and renewal.

▶ Convergence: Destruction as purification. A second chance at civilization.

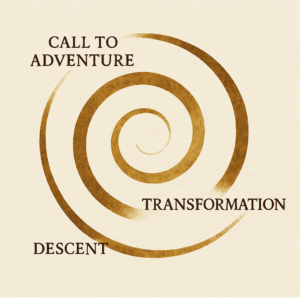

4. Hero’s Descent into the Underworld

- Orpheus, Inanna, Heracles, Jesus, and Dante travel into realms of death and return.

- In religions, this often becomes a motif of resurrection or spiritual rebirth.

▶ Message: Transformation comes through contact with death or darkness.

5. Sacrifice and Redemption

- Prometheus suffers for giving fire to humans.

- Jesus suffers to redeem sin.

- Odin sacrifices himself on Yggdrasil for wisdom.

▶ Thread: Divine suffering imparts knowledge, power, or salvation to humanity.

Myth vs. Religion: The Function Divide

While myths and religious narratives often share themes, their purposes tend to diverge:

| Function | Mythology | Religion |

|---|---|---|

| Explanatory | Why thunder exists, how the world began | Why suffering exists, what follows death |

| Cultural identity | Hero myths unify tribal identity | Sacred texts define moral law |

| Practice | Stories are told or acted out | Stories are ritualized, institutionalized |

| Flexibility | Mutable, reinterpreted, localized | More fixed, canonized, systematized |

Myths are often fluid and plural, coexisting with other traditions. Religions, especially monotheistic ones, tend toward doctrinal centralization.

When Religion Becomes Myth (and Vice Versa)

Time changes everything. What one generation calls faith, another may call folklore.

- The Greek pantheon was once religion—now it’s “mythology.”

- Some Hindu epics are treated as myth by scholars, but lived as religion by believers.

- Even Christian narratives (e.g., the Book of Revelation) are studied mythologically for symbolic motifs.

In reverse, myths are revived through spiritual reinterpretation—like neo-paganism, archetypal psychology, or new age rituals.

▶ Borderline case: Is “myth” simply religion without believers?

Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell: The Psychology of Myth as Religion

In the 20th century, thinkers like Jung and Campbell blurred the line entirely.

In the 20th century, thinkers like Jung and Campbell blurred the line entirely.

- Jung saw myth as expressions of archetypes—universal patterns in the collective unconscious.

- Campbell argued that all religions tell the same basic story: the Hero’s Journey.

In this view, religious narratives are psychological blueprints, not literal truths. God becomes a symbol of wholeness; sin, a metaphor for inner division.

▶ Implication: Myth is not outdated science—it’s the symbolic language of the psyche.

Science and Myth: Different Questions

Science answers how, mythology and religion answer why.

Science answers how, mythology and religion answer why.

- Why is there suffering?

- What makes life meaningful?

- How should we live?

Religions encode these answers in divine law; myths in metaphor. But both act as meaning engines for human experience. And both evolve.

Even today, space exploration, AI, and virtual worlds generate new myths: the Singularity, the AI god, the colonization of Mars. These modern narratives echo old motifs—transcendence, creation, fall, return.

TL;DR

- Myths and religions share symbolic structures—creation, sacrifice, descent, flood.

- Mythology is narrative; religion adds practice and doctrine.

- Over time, myths can become religions—or vice versa.

- Jung and Campbell reframed both as expressions of universal inner patterns.

- In a secular age, myth may outlive religion as a framework for meaning.

References

- Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press.

- Jung, C. G. (1969). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton.

- Eliade, M. (1957). The Sacred and the Profane. Harcourt.

- Leeming, D. A. (1990). The World of Myth. Oxford University Press.

- Hamilton, E. (1942). Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes.

- Doniger, W. (2009). The Hindus: An Alternative History. Penguin.

Discussion

If myths and religions tell the same stories in different forms—what do they reveal about us that science never can?