You blank out during a test. Forget your lines on stage. Can’t recall your PIN when the ATM stares back at you. We often say stress “blocks” the brain—but what’s really going on? Neuroscience offers a layered answer involving cortisol, adrenaline, and how different types of memory interact under pressure. Let’s explore whether stress erases memory, rewires it, or something stranger altogether.

The Biology of Stress: Cortisol and Adrenaline in Action

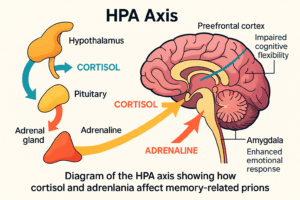

When you’re under pressure—whether facing a lion or a job interview—your brain activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. This triggers two primary responses:

When you’re under pressure—whether facing a lion or a job interview—your brain activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. This triggers two primary responses:

- Adrenaline: fast-acting, boosts heart rate, dilates pupils, sharpens reflexes.

- Cortisol: slower but longer-lasting, increases glucose in the bloodstream, suppresses non-essential functions (like digestion), and modulates brain activity.

These hormones alter how your brain encodes, stores, and retrieves memory—not always for the worse.

Memory Is Not One Thing

To understand stress’s impact, we have to distinguish types of memory:

| Memory Type | Description | Brain Region |

|---|---|---|

| Working Memory | Short-term holding of info (e.g. a phone number) | Prefrontal cortex |

| Declarative Memory | Facts, events, conscious recall | Hippocampus |

| Procedural Memory | Habits, skills, muscle memory | Basal ganglia, cerebellum |

| Emotional Memory | Feelings tied to experiences | Amygdala |

Stress does not affect all these systems equally. That’s why you may forget your speech (declarative) but still instinctively hit the brake (procedural).

Stress Impairs Working Memory First

High cortisol levels impair the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for logic, decision-making, and working memory. That’s why you may:

- Struggle to focus on instructions

- Forget what you were saying mid-sentence

- Freeze during presentations

This phenomenon is sometimes called “mind blank”—the subjective feeling that the brain has gone offline. In reality, the brain is still active, but attention is fragmented by stress signals.

But Stress Also Strengthens Certain Memories

Surprisingly, stress doesn’t just erase—it can also enhance memory, especially for emotional or survival-relevant events.

- The amygdala, which processes fear and emotional salience, becomes hyperactive under stress.

- This boosts the encoding of emotionally charged events, making them more vivid and harder to forget.

That’s why people remember where they were during traumatic events with eerie clarity—a phenomenon known as “flashbulb memory.”

▶ Conclusion: Stress narrows the focus of memory. You lose peripheral detail, but encode the core emotion more deeply.

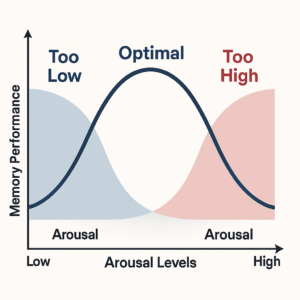

The “U-Curve” of Stress and Performance

Not all stress is bad. The Yerkes-Dodson Law describes a U-shaped curve:

Not all stress is bad. The Yerkes-Dodson Law describes a U-shaped curve:

- Too little arousal → boredom, inattention

- Optimal arousal → peak focus, enhanced memory

- Too much stress → panic, poor recall

This explains why mild stress during studying can help retention—but overwhelming stress during exams can sabotage it.

Chronic Stress and Memory Decline

While acute stress can be beneficial in small doses, chronic stress is another story. Prolonged exposure to high cortisol levels can:

- Shrink the hippocampus, reducing your ability to form new memories\

- Disrupt sleep, further impairing memory consolidation

- Increase inflammation, affecting brain plasticity

Studies show that people with PTSD or long-term anxiety often exhibit memory impairments and reduced hippocampal volume¹.

▶ Translation: When stress is constant, the brain literally remodels itself—to your disadvantage.

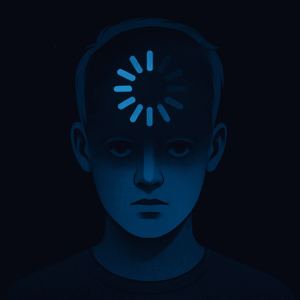

Mind Blank: Freezing, Fleeing, or Filtering?

The “mind blank” is not just forgetting—it’s a protective cognitive freeze. When the brain senses extreme threat, it may:

The “mind blank” is not just forgetting—it’s a protective cognitive freeze. When the brain senses extreme threat, it may:

- Prioritize reflexes over thought (survival mode)

- Suppress irrelevant data to focus on immediate risk

- Interrupt working memory to reduce vulnerability

This is why people “go blank” during public speaking, performances, or danger. The brain reallocates its resources from reflection to reaction.

▶ Analogy: It’s like your computer closing tabs to preserve CPU during a crash.

Coping Mechanisms: How to Protect Memory Under Stress

Can we buffer our brains from stress-induced memory failure? Yes—with both preparation and physiology:

1. Train Under Pressure

Simulate stressful conditions (e.g., mock interviews) to build stress tolerance.

2. Retrieval Practice

Strengthen memory retrieval through repetition and recall—not just re-reading.

3. Breathing & Grounding

Regulate the vagus nerve through deep breathing to lower cortisol levels.

4. Sleep & Nutrition

Memory consolidation depends on REM sleep and glucose availability.

5. Cognitive Reappraisal

Reframe stress as challenge, not threat—changing perception modulates hormonal response.

Stress and False Memories

Interestingly, stress doesn’t just affect memory strength—it can also distort it. Under high stress, people are:

- More prone to misremembering details

- More susceptible to suggestibility

- More likely to “fill in gaps” with plausible—but incorrect—information

This has real-world implications in eyewitness testimony, where accuracy drops significantly under stress².

When Forgetting Is Adaptive

Sometimes, “forgetting” under stress is not a bug—it’s a feature.

- The brain suppresses certain memories to prevent overload.

- Traumatic amnesia may protect psychological stability.

- Memory reconsolidation allows for editing painful events over time.

In evolutionary terms, forgetting the horror while remembering the lesson helps survival without paralysis.

TL;DR

- Stress affects memory selectively, weakening working memory but enhancing emotional encoding.

- Cortisol impairs the prefrontal cortex; adrenaline boosts amygdala sensitivity.

- The “mind blank” is a real cognitive freeze—often protective.

- Chronic stress damages brain structure, while acute stress can sharpen focus.

- Strategies like retrieval practice, breathing, and mindset shifts can protect memory under pressure.

References

- McEwen, B. S., & Sapolsky, R. M. (1995). “Stress and cognitive function.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 5(2), 205–216.

- Deffenbacher, K. A. (1983). “The Influence of Arousal on Reliability of Eyewitness Testimony.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(3), 449–459.

- Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). “Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 410–422.

- Joëls, M., Pu, Z., Wiegert, O., Oitzl, M. S., & Krugers, H. J. (2006). “Learning under stress: how does it work?” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(4), 152–158.

Discussion

If stress doesn’t block the brain but redirects it—how can we learn to aim it more effectively?