What if the final backup isn’t just for your files—but for your mind?

The idea of digital immortality sounds like a sci-fi trope pulled from Black Mirror or Altered Carbon, but it’s increasingly part of real scientific and philosophical debate. From Silicon Valley labs to transhumanist forums, the question is no longer just “Can we upload a brain?” but “What does it mean to survive in data?” Is consciousness something we can encode? If we recreate your memories, your voice, even your sense of humor—do we get you?

We live in an age where memory is cheap, storage is vast, and identity is fluid. Our smartphones already remember more birthdays than we do. Our photos outlive our presence. But turning a person into a digital entity? That’s a leap from archiving to becoming. And unlike cloud storage, there’s no Ctrl+Z for the soul.

The challenge, of course, is that we’re not just meat computers. We are story-driven, emotion-saturated, ever-evolving narratives of experience. Copying that? It’s like trying to capture a symphony by photographing the sheet music.

And yet… we try.

The Dream: Uploading Minds and Escaping Mortality

Immortality has never gone out of fashion—it’s just changed format.

In ancient myths, heroes drank ambrosia, made pacts with gods, or hid their souls in magical objects. Today’s equivalent? Terabytes and neural scans. Instead of elixirs, we have Elon Musk’s Neuralink, Nectome’s “membrane preservation,” and Google’s deep learning models quietly mapping language, memory, and behavior. Immortality is no longer the domain of wizards—it’s a line item in R&D budgets.

At the heart of it lies a radical promise: what if death is just a technical problem? If the brain is a pattern of synaptic activity—a matrix of thoughts, memories, habits—then maybe, in principle, it can be replicated. Stored. Simulated. Rebooted.

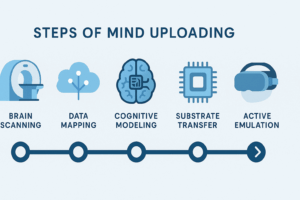

This is the essence of the “mind-uploading hypothesis”: scan the brain at high enough resolution, translate its structure into code, run that code on a powerful enough machine—and voilà, digital you. Not a clone. Not a simulation. You. Or something terrifyingly close.

code, run that code on a powerful enough machine—and voilà, digital you. Not a clone. Not a simulation. You. Or something terrifyingly close.

Proponents call it liberation from biology. Critics call it philosophical nonsense. After all, uploading your brain is not like uploading a file—it’s like trying to upload a candle flame. You might capture its shape, but can you catch its light?

Still, the idea persists. Because behind all the technology is an ancient desire: not just to live longer, but to live beyond.

The Science: Mapping the Brain, Bit by Bit

If you want to upload a mind, you first need to know what a mind is—and where it lives. Spoiler: it’s not just the pink jelly in your skull.

Neuroscience has made stunning progress in mapping the human brain. We’ve identified over 180 cortical areas, traced millions of neural pathways, and even built a partial connectome—a wiring diagram of who’s talking to whom inside your head. But we’re still playing with shadows.

Comparative Table: Simulation vs. Upload vs. Emulation

| Feature | Simulation | Upload | Emulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Data | Incomplete | Partial | Full |

| Consciousness | Absent | Possible | Probable |

| Interaction | Limited | Dynamic | Complex |

| Example | Chatbot | Mindclone | Whole Brain Emulation |

Each human brain has roughly 86 billion neurons and 100 trillion synaptic connections. And it’s not just about where they are—it’s about how they fire, how they change over time, how they encode your first kiss, your mother’s voice, your fear of wasps.

Projects like the Human Connectome Project and Blue Brain are trying to model brain regions at incredible detail, down to the molecular level. But even the most advanced simulations today operate at the level of mouse brains—and only in slices. Your brain is not just big; it’s contextual, plastic, embodied. It’s shaped by your body, your environment, your language.

And yet… progress is real. Brain-computer interfaces can already decode words, cursor movements, even emotional states. We’re learning to read thoughts as if they were Morse code. Give it time—and a few more revolutions in computing power—and the idea of digitizing consciousness starts to look less like science fiction and more like a research proposal with a Gantt chart.

Still, mapping a brain is not enough. The real question is: can a map ever be the territory?

The Copy Problem: Is It Still You?

Let’s say we do it. We scan your brain—every synapse, spike pattern, and biochemical whisper. We upload the whole thing onto a quantum-optimized neural lattice in the cloud. You blink. You’re alive.

But are you?

This is where the wires start to tangle—not technically, but philosophically. If we build a perfect digital version of your mind, does that new “you” have your consciousness? Or is it just a really good impersonator, mimicking your memories, your quirks, your irrational fear of garden gnomes?

From the perspective of the simulation, everything checks out. It thinks it’s you. It remembers that time you cried during Blade Runner 2049. It laughs at the same memes. But you, the biological you, are still here—thinking, breathing, caffeinating.

This is the Ship of Theseus in binary: if you replace every atom with a byte, do you still have a self? Or just a ghost in a USB stick?

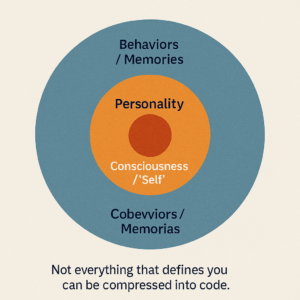

Philosophers like Derek Parfit argue that identity is not what matters—continuity is. If your memories, values, and personality persist, maybe that’s enough. Others, like John Searle, say no amount of data replication can produce real understanding. Consciousness, in this view, is not software—it’s substrate-dependent.

This leads to the hardest of the hard problems: is consciousness transferable, or just copyable? And if it’s just a copy… is death still unavoidable?

We may one day upload minds to machines—but whether your self comes along for the ride? That’s still up for grabs.

Substrate Matters: Biology vs. Silicon

Here’s a thought experiment: If you bake a cake using a 3D printer, is it still a cake? Sure, it might look like one. It might even taste like one. But something—some texture, some warmth—feels off. Now replace “cake” with “consciousness.” That’s the core of the substrate debate.

Our brains are not digital. They’re not even analog in the classic sense. They are biological storms of ions, chemistry, and quantum noise, forged over millions of years of evolutionary kludges. Neurons fire not just because of electricity, but because of glial support cells, temperature fluctuations, and possibly even quantum coherence (if you ask the Penrose crowd).

Silicon-based machines, on the other hand, operate on binary logic. They can simulate brain activity—model it with staggering accuracy—but can they instantiate it? Can they be conscious, or are they forever condemned to zombiehood—mimicking human behavior with no internal experience?

This is where theories clash:

- Strong AI proponents argue that consciousness is computational. It doesn’t matter what the substrate is, as long as the function is preserved. If a computer behaves like a brain, it is a brain.

- Biological essentialists believe consciousness emerges from the unique qualities of biological matter. They argue that the wetware matters, and no software—no matter how sophisticated—can replicate that emergent spark.

There’s even a middle ground: theories suggesting that consciousness might require a certain kind of complexity or feedback loop, regardless of the material. But we still have no empirical way to test if a system is truly conscious—or just saying it is.

In short: we can upload behavior, but uploading awareness might be like trying to download sunlight.

So before we plug our souls into a server, maybe we need to ask: is feeling codeable? Or does it need a pulse?

Continuity and Memory: What Makes “You,” You?

Imagine waking up in a lab, in a perfect copy of your body. Same memories, same personality, same favorite Blade Runner quote. But… you also still exist—back in your original body. So which one is you?

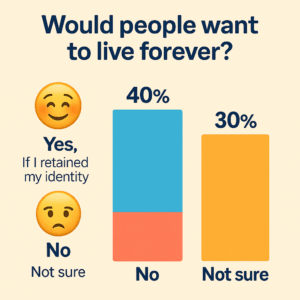

This is the philosophical minefield of personal identity—a centuries-old debate made painfully relevant by the idea of digital immortality.

From Locke to Parfit, thinkers have tried to pinpoint what constitutes the self. Is it your memory? Your continuity of consciousness? Or just your body in motion through time? The uploading hypothesis messes with all of that.

Let’s say we scan your brain—every synapse, every neurotransmitter—and simulate it on a quantum supercomputer. The digital you wakes up and says: “Hey, I’m still me!” But are they? Or is that just a convincing clone, doomed to philosophical loneliness?

Two major scenarios emerge:

- Gradual transfer – Your consciousness is slowly migrated, neuron by neuron, like replacing planks on a ship. This echoes the Ship of Theseus: is the resulting entity still you, or just a replica with good PR?

- One-shot upload – Your brain is copied, and the copy is activated. The original… is switched off. This feels more like death followed by duplication, rather than immortality. You’re gone—but your data lingers.

And here’s the existential kicker: even if the copy feels like you, that doesn’t mean you continue. You might be as dead as a dial-up modem while your twin lives on in the cloud, writing blog posts and liking cat videos.

This dilemma haunts not just philosophers but transhumanists, AI ethicists, and sci-fi writers. It forces us to ask:

Is the self a stream or a snapshot?

We’ve always assumed “you” is a continuous thing. But in a world of uploads, maybe we’re looking at a network of versions—each real, none original. A terrifying or liberating thought, depending on your metaphysics and caffeine level.

Ethical Quagmires: Clones, Control and Capitalism

Let’s say we can upload minds. We’ve figured out the tech, the metaphysics, and even the snack breaks during neural scanning. What now?

Well… now we have problems.

Uploading a human consciousness is not just a technical leap — it’s a socioeconomic earthquake. Because once minds become software, we’re not just talking about life extension. We’re talking about:

become software, we’re not just talking about life extension. We’re talking about:

- Ownership: Who owns the uploaded you? Is it you, the original biological mind? Or the corporation that provided the server space and charged $49.99/month for emotional backups?

- Clones: Can you make copies of yourself? Run two versions simultaneously? One to work, one to binge The Expanse? Which one is legally “you”? And what happens if one sues the other?

- Rights: Do uploads have rights? Are they citizens? Can they vote? Marry? What if your digital self wants to be deleted — do they have the right to die?

It’s easy to imagine a techno-utopia where minds live in blissful virtual gardens, reading Borges and eating simulated tiramisu. But let’s be honest — if history tells us anything, it’s that someone will find a way to monetize immortality.

Imagine working 24/7 as a data analyst inside a corporate server, with no sleep, no pay, and no escape. Eternal gig economy.

Governments, corporations, and rogue AIs might treat uploaded minds as intellectual property, subject to license agreements and user terms you never actually read. Your afterlife may come with banner ads.

We’re entering philosophical Black Mirror territory here: what does consent mean when a consciousness can be copied? What if someone else uploads you, without permission? Is that theft? Identity fraud? Or just a digital doppelgänger?

And what if the backup becomes smarter, kinder, better than the original?

Digital immortality could fracture society along new lines of inequality — between the uploaded elite and the mortals below. Or, optimistically, it might democratize wisdom, letting minds from all walks of life exist beyond the limits of biology.

But make no mistake: ethics won’t be a footnote. They’ll be the main event.

A New Kind of Legacy: What We Leave Behind

We used to leave behind books, buildings, maybe a few memorable dinner parties and some awkward family photos. Legacy meant stories whispered down generations — or, if you were lucky, a name on a library.

But in a world where minds can be digitized, legacy becomes… interactive.

Your grandchildren might not just remember you — they might talk to you. Debate you. Ask your opinion on quantum gravity. You, as in: the uploaded you, chilling in a server room, sipping virtual coffee, and still annoyed about the Oxford comma.

Legacy, once bound by memory and biology, becomes code — executable, editable, eternal.

This redefines what it means to live on. Instead of echoing through the memories of others, you become a perpetual presence, an entity that evolves alongside humanity. You’re no longer just a story. You’re a participant.

But is that still you? Or just a well-trained mimic, quoting your habits, quirks, and favorite pizza toppings?

There’s beauty in the fragility of the human legacy — the handwritten note, the fading photograph. Will digitizing it all make us more than human, or less?

Still, the promise is tempting: not just to be remembered, but to contribute long after we’re gone. To write, teach, explore — as an algorithm with soul-shaped data.

If we play this right, the future might not just be about living forever — but about staying relevant.

Immortality, it turns out, might be less about conquering death, and more about changing how we define life.

TL;DR

- Digital immortality is no longer just science fiction — it’s an active field in neuroscience, AI, and ethics.

- Uploading a mind may become technically feasible, but recreating consciousness remains philosophically unresolved.

- The line between memory, personality, and identity blurs as we model human thought in data.

- Projects like mind uploading, legacy bots, and neural interfaces are early steps toward post-biological existence.

- Even if we can simulate a soul… can we ever transfer one?

- The question may not be “Can we live forever?” but “What does it mean to be alive?”

References

- Kurzweil, R. (2005). The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. Viking Press.

- Hayworth, K. J. (2012). “Electron imaging technology for whole brain neural circuit mapping.” International Journal of Machine Consciousness, 4(1), 5–12.

- Koene, R. A. (2012). “Embracing reality: The case for substrate-independent minds.” Journal of Consciousness Studies, 19(1–2), 112–138.

- Metzinger, T. (2010). The Ego Tunnel: The Science of the Mind and the Myth of the Self. Basic Books.

- Bostrom, N. (2003). “Are You Living in a Computer Simulation?” Philosophical Quarterly, 53(211), 243–255.

- Roache, R., & Savulescu, J. (2014). “Artificial intelligence and the future of the human mind.” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 23(1), 80–87.